WILLIAM GAZECKI ON DOCUMENTARIES

Information to young people on their decision-making process

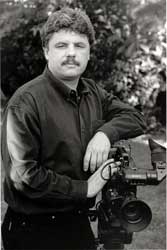

Academy Award-nominated and Emmy-award winning documentary filmmaker William Gazecki got his start in the movie industry where he helped produce albums for such talents as The Doors, Bette Midler, Joe Cocker and Leo Sayer. He then went into television where he won awards for his production work on shows such as “St. Elsewhere,” “Hill Street Blues,” and “thirtysomething,” before finding his passion as a documentary/independent filmmaker. Recently, besides his ongoing film projects, Mr. Gazecki has been involved in starting a new production company called OpenEdge Media, based in West Los Angeles. Here is some of his advice to young people starting out in the documentary world:

Documentary films are a very attractive alternative to feature films. The stakes are not as high because the money is not as large, so the opportunities are actually easier to come by, and the risk is not so great.. Thus, when you really get down to making films, getting them funded, and produced, you’re not dealing with twenty to one hundred million dollars, you’re dealing with one thousand to half a million dollars. Getting into documentaries can be viable and attractive for a variety of reasons.  The nice thing about it is that it’s still filmmaking. It’s still that craft. It doesn’t carry with it all of the extreme challenges that feature filmmaking brings. I used to see people getting into documentaries because they thought it was a stepping stone to feature films. I personally don’t like that because I think the documentary genre deserves people that are there for the right reasons. They’re there because they appreciate reality; they appreciate the real things in life that are interesting and fascinating.

The nice thing about it is that it’s still filmmaking. It’s still that craft. It doesn’t carry with it all of the extreme challenges that feature filmmaking brings. I used to see people getting into documentaries because they thought it was a stepping stone to feature films. I personally don’t like that because I think the documentary genre deserves people that are there for the right reasons. They’re there because they appreciate reality; they appreciate the real things in life that are interesting and fascinating.

They want to share that; they want to create vehicles to disseminate these facets of life in a film genre, in the film medium.You have to educate yourself in the craft, but the craft is very diverse. I chose to take a highly technical hands-on approach, but you don’t have to do that. You can be more of a financier-producer type. Once you decide that documentary filmmaking is for you for whatever reasons, you have to educate yourself in the elements of the industry. And a lot of that is just vocabulary to begin with. You have to know the terms: what is a producer, a director, a distributor, a financier, an editor, a cameraman, or a grip? You need to learn the technical terms and the avocations; you need to educate yourself in what the job descriptions are for each position and how they work together. From there you can make a more intelligent choice as to what kind of role you want to play.The story is the bottom line.

Once you’ve made your choices and once you’ve decided on what you want to do and where you’re going, telling the story is number one. You don’t want to put your own personality too far in front or too prominently in the mix. How you begin is extremely important because the first  moment is a thread to the next moment and so on. You set a tone and you create a moment. Films are about a string of moments.The young filmmaker can go wherever they think that they themselves can speak through a medium. For example, if you really love sports, what athletes and the sports business is about, and the dynamics within a team and between teams, then you might become a sports documentarian. If you’re going to be a full time filmmaker, you’ve got to find projects that you feel are either relevant or appealing to some larger group and that’s a personal choice. You have to pay attention and spend time considering what would find a home in the marketplace; otherwise it may be very difficult for you to financially sustain yourself, unless you have independent means. The other side of documentary filmmaking is to be supported by foundations and the non-profit world, which is very common.

moment is a thread to the next moment and so on. You set a tone and you create a moment. Films are about a string of moments.The young filmmaker can go wherever they think that they themselves can speak through a medium. For example, if you really love sports, what athletes and the sports business is about, and the dynamics within a team and between teams, then you might become a sports documentarian. If you’re going to be a full time filmmaker, you’ve got to find projects that you feel are either relevant or appealing to some larger group and that’s a personal choice. You have to pay attention and spend time considering what would find a home in the marketplace; otherwise it may be very difficult for you to financially sustain yourself, unless you have independent means. The other side of documentary filmmaking is to be supported by foundations and the non-profit world, which is very common.

This is a personal process where you learn to not compromise yourself and not sell out to the checkbook. But at the same time, you must make films that you feel you have a personal relationship, with a personal investment in.  I’m a cameraman; my specialty is handheld camerawork because I like to capture the moment. I’m a fan of verite — hand-held work is a real intuitive gut-level thing, and that’s what I’m good at. I’m a director/cameraman which is what a lot of documentarians are. One of things about documentaries is that you’re often shooting with one camera. And if you’re shooting with one camera, let’s say you’re shooting an interview. You’re almost always going to cut that interview down. And if you cut that interview down you’re going to have jump cuts. And if you have jump cuts you have to cover it with something. So when you’re shooting you have it to think coverage. You’ve got to think reverses, b-roll and graphics, something to cut away to. How are you going to string this together when you’re using little bits and pieces later on? The thing about editing is that it’s very important but it needs to appear as if nobody did anything. The best films are films that you think essentially came out of the camera, and that’s what many people think. The key word in all of this is seamless. The viewer should not be aware of any technique at all. And that is something that is really a fine art of the craft. It’s the sign of a really accomplished filmmaker if you can look at a film and not see the filmmaker.

I’m a cameraman; my specialty is handheld camerawork because I like to capture the moment. I’m a fan of verite — hand-held work is a real intuitive gut-level thing, and that’s what I’m good at. I’m a director/cameraman which is what a lot of documentarians are. One of things about documentaries is that you’re often shooting with one camera. And if you’re shooting with one camera, let’s say you’re shooting an interview. You’re almost always going to cut that interview down. And if you cut that interview down you’re going to have jump cuts. And if you have jump cuts you have to cover it with something. So when you’re shooting you have it to think coverage. You’ve got to think reverses, b-roll and graphics, something to cut away to. How are you going to string this together when you’re using little bits and pieces later on? The thing about editing is that it’s very important but it needs to appear as if nobody did anything. The best films are films that you think essentially came out of the camera, and that’s what many people think. The key word in all of this is seamless. The viewer should not be aware of any technique at all. And that is something that is really a fine art of the craft. It’s the sign of a really accomplished filmmaker if you can look at a film and not see the filmmaker.

Digital technology is completely in support of that, because you can essentially now have all of your postproduction tools at your fingertips in one room, which is unprecedented, something that’s only been true in the last 3 or 4 years. Digital technology affords low cost access to production, but it’s really just a tool. The real meat is in the idea, in the concept.

A lot of directors are technically preoccupied, and they don’t realize that the main part of a director’s job is dealing with people. You have to know how to deal with  your subject — how to talk to them and how to get them to appear on camera without being nervous, without being afraid. Sometimes you have to work just to get them on camera. This is especially true if you’re doing controversial subjects where you’re going against an adversary, like the district attorneys in my film, “Reckless Indifference,” who did not want to appear, so getting them on tape was a complex process, and with my film, “WACO: The Terms of Engagement,” where we couldn’t get the FBI to appear so we had to find a way to do the film without the FBI’s cooperation. Learning how to deal with those human logistics has nothing to do with technology, and it’s a very important part of the process. My documentaries deal with people and society — human actions and histories and feelings, what makes a human being do what they do, what makes a society go in the direction it goes, and the evolution of culture.

your subject — how to talk to them and how to get them to appear on camera without being nervous, without being afraid. Sometimes you have to work just to get them on camera. This is especially true if you’re doing controversial subjects where you’re going against an adversary, like the district attorneys in my film, “Reckless Indifference,” who did not want to appear, so getting them on tape was a complex process, and with my film, “WACO: The Terms of Engagement,” where we couldn’t get the FBI to appear so we had to find a way to do the film without the FBI’s cooperation. Learning how to deal with those human logistics has nothing to do with technology, and it’s a very important part of the process. My documentaries deal with people and society — human actions and histories and feelings, what makes a human being do what they do, what makes a society go in the direction it goes, and the evolution of culture.

I’m currently making three theatrical documentaries: the first is “Crop Circles: Quest For Truth.” I think that Crop Circles are one of the most unrecognized  significant unexplained phenomena in the world. The premise of the second film, “Into the Mystic,” about the history of psychedelics, is that for thousands of years, in pretty much every indigenous culture throughout history, sacred psychotropic plants have been utilized to help guide and manage society. “The Orphans of Duplessis,” the third documentary I’m in production on, is very much like my film “WACO: The Rules of Engagement,” in that it’s the unraveling of a major unknown injustice. It involves the Catholic Church in a very fundamental way. It concerns the misapplication of many of very fundamental religious practices. It shows how power corrupts. Children were involved and children were severely abused. Those children are now grown adults and their plight has gone unrecognized. They have had no closure, or even an apology from either the Canadian government or the Catholic Church. That’s all they really want. The way we’re approaching “The Orphans of Duplessis” is to take the most compassionate, highest road. What we’re trying to do is a very empathetic piece to show where love went wrong, and how much harm greed can cause. It’s great drama – a truly dramatic story.

significant unexplained phenomena in the world. The premise of the second film, “Into the Mystic,” about the history of psychedelics, is that for thousands of years, in pretty much every indigenous culture throughout history, sacred psychotropic plants have been utilized to help guide and manage society. “The Orphans of Duplessis,” the third documentary I’m in production on, is very much like my film “WACO: The Rules of Engagement,” in that it’s the unraveling of a major unknown injustice. It involves the Catholic Church in a very fundamental way. It concerns the misapplication of many of very fundamental religious practices. It shows how power corrupts. Children were involved and children were severely abused. Those children are now grown adults and their plight has gone unrecognized. They have had no closure, or even an apology from either the Canadian government or the Catholic Church. That’s all they really want. The way we’re approaching “The Orphans of Duplessis” is to take the most compassionate, highest road. What we’re trying to do is a very empathetic piece to show where love went wrong, and how much harm greed can cause. It’s great drama – a truly dramatic story.

When I started down the road to become a documentary filmmaker, I took a series of courses at the American Film Institute called “Directors on Directing and Producers on Producing.” All of these guys came in one at a time, all very famous and very successful, and they all said the same thing, “Do what you love.” If you’re making it for money it will only fail, it always does. If you do what you love and do it because you love it, your chances of success increases. Things that are successful are always done because somebody behind it really wanted to do it.

Don’t become a filmmaker unless you’re prepared for a lot of sacrifice, a lot of risk, and putting up with your parents being on your case for not making any money. Filmmakers don’t really have sophisticated social lives and there are a lot of challenges. It’s not always a pretty picture, but in the end it is more than worth it.